Author: Megan Jones (Adv.Dip.NutMed, BHsc.NutMed)

Menopause is a non-pathologic condition occurring in all women and involving the permanent cessation of menses resulting from oestrogen deficiency.[1] Marking a significant transition in a woman's life, the declining oestrogen levels bring about a host of physical and hormonal changes, with symptoms such as hot flushes, mood swings, food cravings and weight gain.[2] The hormonal and bodily changes experienced during menopause can lead to changes in eating behaviours, body image and overall self-perception,[3] while dietary habits during menopause are often subjected to scrutiny.[4]

For many, navigating nutrition during this time can feel like traversing a maze. A quick search for “nutrition during menopause” brings up 53 million results, with advice on what to eat and what to avoid. When looking at the science, however, adopting simple, evidence-based lifestyle changes and developing consistent habits is key when supporting health and wellbeing throughout menopause.[5] Furthermore, maintaining a nutritionally dense, balanced diet with a focus on adequate macronutrition, particularly protein, becomes even more essential when navigating this phase.[6] [7]

Read on as we delve into the importance of consuming enough quality protein during menopause and discover how optimising protein levels can enhance muscle health, support hormonal balance, and contribute to both physical and emotional wellbeing as well.

Metabolic Health in Menopause

As women shift from “perimenopause” status to “postmenopausal”, independent of age, the reduction in circulating oestrogens [8] increases the possibility of developing and arguably worsening insulin resistance. This insulin resistance is also triggered by the slow but progressive cortisol increase typical of ageing. In the liver, high cortisol triggers gluconeogenesis, a process that boosts the liver's production of glucose, which not only reduces insulin secretion and hinders insulin clearance but exacerbates insulin resistance as well.[9] [10] [11] [12] [13]

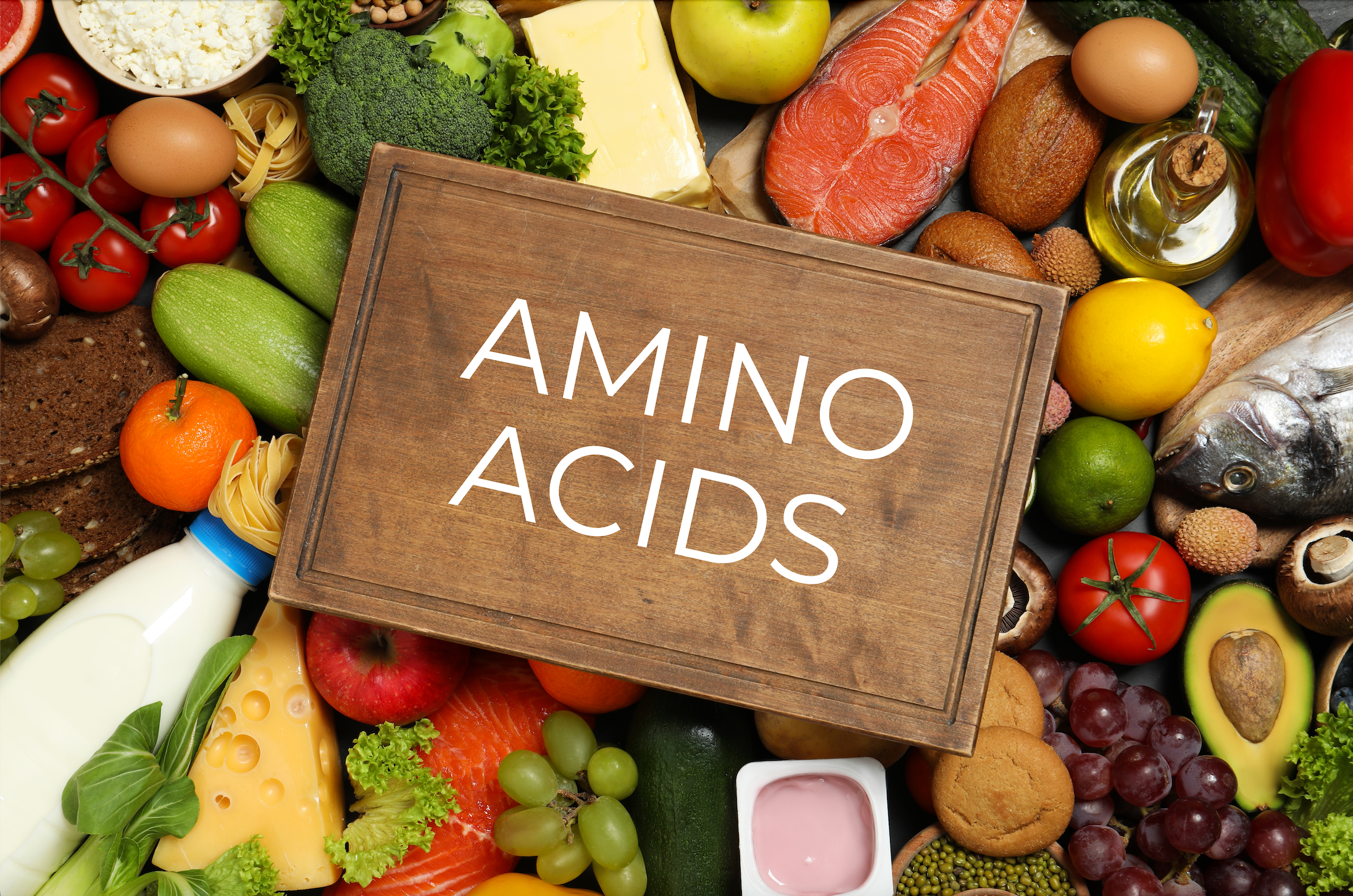

Understanding how dietary choices influence insulin resistance and subsequent metabolic health can significantly improve the quality of life [14] during this transition. A high protein diet can modulate glucose homeostasis by directly stimulating insulin secretion through amino acids such as leucine, isoleucine, valine, arginine, and lysine - all products of protein digestion. A high protein diet can also decrease blood sugar levels and support insulin sensitivity indirectly through incretin release and vagal neuronal pathways, while it can promote satiety via anorectic hormones as well.[15]

Read on to discover what your daily protein intake recommendation might be and how to tailor it to your specific needs for optimal health.

The Importance of Protein During Menopause

Preserving muscle mass and strength

Another significant change during menopause is the gradual, age-related loss of muscle mass, known as sarcopenia.[10] This condition can lead to decreased strength due to difficulty in repair and regeneration of muscle and is linked to higher rates of falls and vertebral fractures,[16] [17] ultimately affecting both quality of life and independence. While global estimates of sarcopenia range from 9.9% to 40.4%, depending on both the definition used and population studied, in menopausal women, sarcopenia prevalence increases with age, affecting 1.4% of those aged 60–69, 4.9% of those aged 70–79, and 12.5% of those aged 80 and older.[18]

To counteract sarcopenia, intake of dietary protein is an important factor. Impacting regulatory proteins and growth factors, while providing the necessary amino acids for muscle repair and growth,[19] [20] it is essential for preserving muscle mass and strength.[21] In fact, by consuming an adequate amount of protein, muscle loss associated with ageing and hormonal changes can potentially be prevented, helping the body maintain physical strength and ability, and overall wellbeing.[12] [22]

The current recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of good-quality protein, balanced in all 9 essential amino acids is 0.8g per kilogram of bodyweight per day, but several studies suggest that higher protein consumption with a 20% increase above the RDA is required to preserve muscle mass and function for those who are postmenopausal.[23] Furthermore, upper and lower extremity functions are impaired in postmenopausal women with protein intake below the RDA.[24]

A clinical trial by Longland et al. published in 2016 revealed that at the long term 5-year follow-up, high protein intake of 1.2g per kilogram of bodyweight per day was associated with beneficial effects on muscle mass and size and bone mass in elderly women.[25] [26] [27] In addition to this, when in a marked energy deficit, combined with a high volume of resistance and anaerobic exercise, consumption of a diet containing 2.4 g protein per kilogram of bodyweight per day was more effective than consumption of a diet containing 1.2 g protein in promoting increases in lean body mass and losses of fat mass.

Supporting bone health

Oestrogen plays a key role in the maintenance of bone density, therefore as its levels decline during menopause, women are at a higher risk of osteoporosis and fractures.[28] Dietary protein is the major structural component of all cells (including bone cells) in the body [29] and is essential for bone health because it promotes the production of collagen, a protein that forms the structural framework of bones.[30] What's more, adequate protein consumption helps with the absorption of calcium and other vital minerals necessary for optimal bone strength.[31]

While the long term 5 year follow-up of a study by Longland et al. showed that high protein intake of 1.2g per kilogram of bodyweight per day was associated with beneficial effects on bone mass in elderly women, a prospective investigation of the Iowa Women’s Health Study showed higher protein intake to be associated with a reduced incidence of hip fracture among more than 40 000 postmenopausal women.[32]

In a 2018 study involving 131 postmenopausal women, those who consumed 5 grams of collagen peptides daily experienced a significant improvement in bone mineral density compared to those who received a placebo.[33]

Managing weight and metabolism

Weight gain is a common concern for menopausal women, often due to a slower metabolism and changes in body composition.[16] Oestrogen is known to suppress appetite, so when its levels begin to decline, the ability to regulate hunger and satiety signals becomes impaired. This can lead to abnormal eating patterns and potential weight management issues, commonly referred to as "appetite dysregulation".[34]

As appetite influences energy intake, an increased intake of dietary protein of 1.2g per kilogram of bodyweight per day, which is satiating and can improve body composition, has been considered highly beneficial for body weight management.[35] [36] [37] Furthermore, there is a consistent body of evidence suggesting that diets higher in protein up to 2.4g per kilogram of bodyweight per day increase energy expenditure due to an increased thermic effect [38] - increasing satiety via the gut hormone PYY which in turn stimulates thermogenesis.[39]

Further highlighting the need for dietary protein during this time, the hormones ghrelin and leptin are also impacted by the changes in both insulin and cortisol associated with menopause. A study of 40 women during different stages of the menopause transition found that for some women, levels of ghrelin increased whilst their leptin levels decreased, potentially contributing to a diminished sense of fullness.[40]

The individual's level of activity also determines the daily protein requirement, with daily protein intake recommended for those engaging in regular physical activity to fall within the mid- to upper ranges of current sport nutrition guidelines (1.4–2.2 g per kilogram of bodyweight per day) for peri- and post-menopausal women, with protein doses evenly distributed, every 3-4 hours, across the day.[41]

Interesting fact: Research from the University of Sydney highlights the 'Protein Leverage Effect,' which indicates that an increased appetite for protein during perimenopause in the years leading up to menopause may lead to overconsumption of other energy forms if protein needs are not met. Adjusting the diet to increase protein and reduce carbohydrates and fats can prevent weight gain and reduce the risk of obesity and cardiometabolic diseases post menopause.[42] [43]

Improving mood and cognitive function

Hormonal fluctuations during menopause can significantly impact mood and cognitive function, manifesting as symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and memory lapses.[44] Focussing on protein intake at this time is important, as it supplies the amino acids required for the synthesis of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, which are vital for mood regulation and cognitive function.[45] [46]

Since post-menopausal females have higher fasting blood measures such as metabolic responses for glucose and insulin, and high glucose values have been reported to negatively impact mood, protein intake 20% above the RDA of 0.8g per kilogram of bodyweight per day becomes crucial for stabilising blood sugar levels, thereby potentially improving mood and supporting metabolic health.

Sources of Protein

Incorporating a variety of protein sources ensures that women in menopause receive all essential amino acids and vital nutrients, supporting overall health. Excellent sources include lean meats, fish, dairy products, eggs, legumes, nuts, seeds, whole grains, and protein supplements, each offering unique benefits like high-quality protein, healthy fats, and additional nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids, calcium, and fibre.

Practical Tips for Boosting Protein Intake

Start with breakfast: Incorporate protein-rich foods like eggs, Greek yogurt, or a protein smoothie into your morning routine.

Spread protein intake throughout the day: Distribute your protein consumption across all meals for optimal absorption. Aim for around 20-30 grams of protein per meal to maintain muscle mass and manage hunger effectively.

Snacking smart: Choose protein-packed snacks such as nuts, seeds, or a boiled egg.

Balance your meals: Ensure each meal includes a source of protein, such as adding chicken to your salad or beans to your soup.

Plan ahead: Prepare protein-rich meals and snacks in advance to make it easier to meet your daily requirements.

Combine plant and animal proteins: Mixing different protein sources can provide a broader range of amino acids and nutrients.

Utilise protein supplements if necessary: If dietary intake is insufficient, protein powders can be a convenient supplement. Choose high-quality options with minimal additives and sugars.

Embracing Protein to Support the Transition

Protein is a vital nutrient for menopausal women, offering numerous benefits from preserving muscle mass and bone health to supporting blood sugar regulation, mood and cognitive function. By prioritising protein throughout each day, and incorporating a variety of protein-rich foods, women can navigate menopause with greater ease and maintain their health and vitality during this transformative stage of life.

References:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9235827/#cit0001

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4539866/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8404323/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36728103/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7663947/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10780928/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8308420/

- https://ajp.amjpathol.org/article/S0002-9440(21)00245-5/fulltext#bib28

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/#:~:text=Cortisol%20acts%20on%20the%20liver,gluconeogenesis%20and%20decrease%20glycogen%20synthesis

- https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2002#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20studies%20of%20the,decreased%20insulin%20clearance%20with%20aging

- https://gremjournal.com/journal/02-03-2023/metabolic-syndrome-insulin-resistance-and-menopause-the-changes-in-body-structure-and-the-therapeutic-approach/

- https://gremjournal.com/journal/02-03-2023/metabolic-syndrome-insulin-resistance-and-menopause-the-changes-in-body-structure-and-the-therapeutic-approach/#:~:text=As%20women%20shift%20from%20the,this%2C%20further%20promotes%20insulin%20resistance

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10794094/#:~:text=Estrogen%20is%20a%20protective%20shield,circulating%20estrogen%20in%20the%20blood

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8500369/

- https://physoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.14814/phy2.15577

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27886695/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27897402/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30052707/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9998208/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9235827/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25082206/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9235827/

- https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/14/8718

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24522467/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33201025/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9235827/#cit0095

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26817506/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5643776/

- https://journals.lww.com/nutritiontodayonline/fulltext/2019/05000/optimizing_dietary_protein_for_lifelong_bone.5.aspx

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507709/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22139564/#:~:text=In%20addition%20to%20calcium%20in,bone%20mineral%20density%20or%20content

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9925137/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5793325/#:~:text=In%20conclusion%2C%20the%20findings%20of,in%20postmenopausal%20women%20with%20age%2D

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22281161/

- https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.17290?af=R

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7539343/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8468854/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8468854/#B12-nutrients-13-03193

- https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/21/4671#B195-nutrients-15-04671

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2311418/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15502783.2023.2204066#abstract

- https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2022/10/13/prioritising-protein-during-perimenopause-may-ward-off-weight-gain.html

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00178.x

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9889489/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9822089/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4728667/